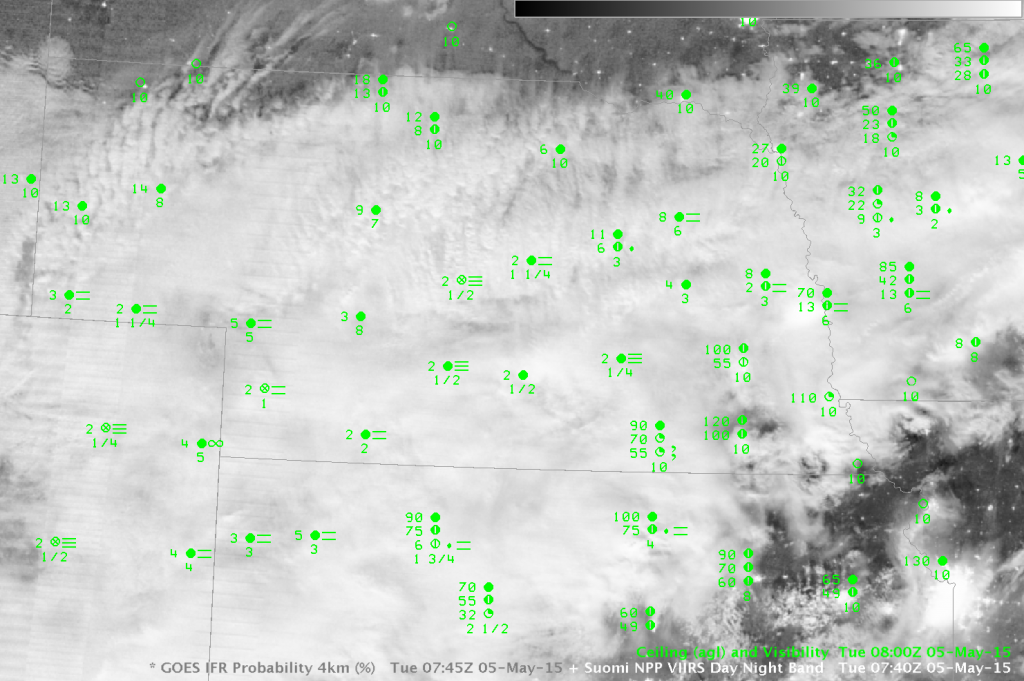

Dense Fog developed over the Hastings, Nebraska WFO overnight, leading to the issuance of Dense Fog Advisories. The GOES-R IFR Probabilities, above, show a steady increase in probabilities over the night as the fog develops. The relatively flat nature of the IFR Probability field is characteristic of GOES-R IFR Probabilities that do not include information from satellite (that is, only model fields are being used here to educe IFR probabilities). IFR Probability fields are a fused product, typically blending information from model fields and from satellite data. However, this was a case of fog developing under an extensive cirrus shield so that satellite data were not used as a predictors. The 10.7µm – 3.9µm Brightness Temperature Difference field, shown below, gives no information about surface conditions. That the IFR Probability fields neatly overlap the region of developing IFR conditions is testimony to the accuracy of the model field in simulating the lower part of the troposphere.

When only model data are used, as above, features in the field that are parallel to surface topography contours can become evident in the GOES-R IFR Probability fields. This is related to interpolation of the lowest 1000 feet of model relative humidity fields (moisture information that is used as a predictor in the computation of the IFR Probability) in regions of sloping topography.

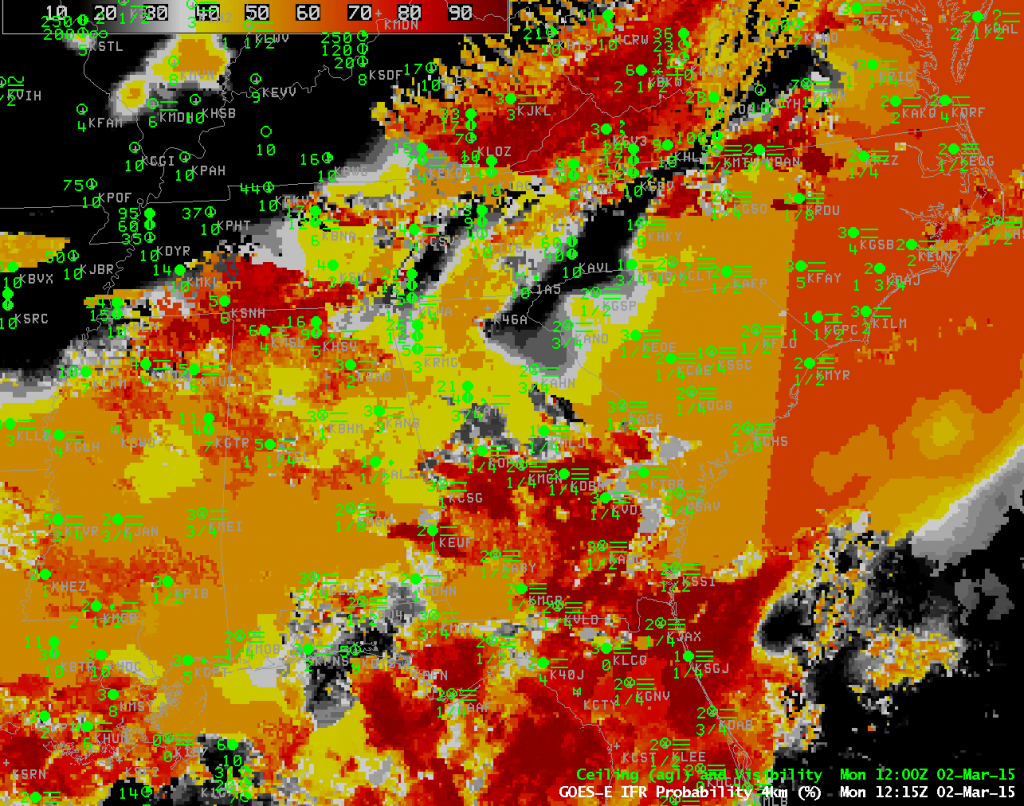

In the animation above, note that the IFR Probabilities increase in the final frame. Over most of the scene, at 1215 UTC, the sun has risen and Daytime Predictors are being used to compute IFR Probabilities. (The dividing line between Daytime — to the east — and nighttime — to the west — is visible stretching north-northwest to south-southeast from the extreme northeast corner of Colorado). IFR Probabilities are somewhat higher during the day (compared to night) because visible imagery is incorporated into the satellite predictors; more accurate cloud clearing means that IFR Probabilities increase just a bit.

GOES-13 Brightness temperature difference fields (10.7 µm – 3.9 µm) over the Great Plains, 0630-1300 UTC, 5 May 2015 (Click to enlarge)

Suomi NPP overflew Nebraska, giving a view of the extensive cirrus shield. The Day Night Band gave crisp imagery as the Moon was very nearly full.