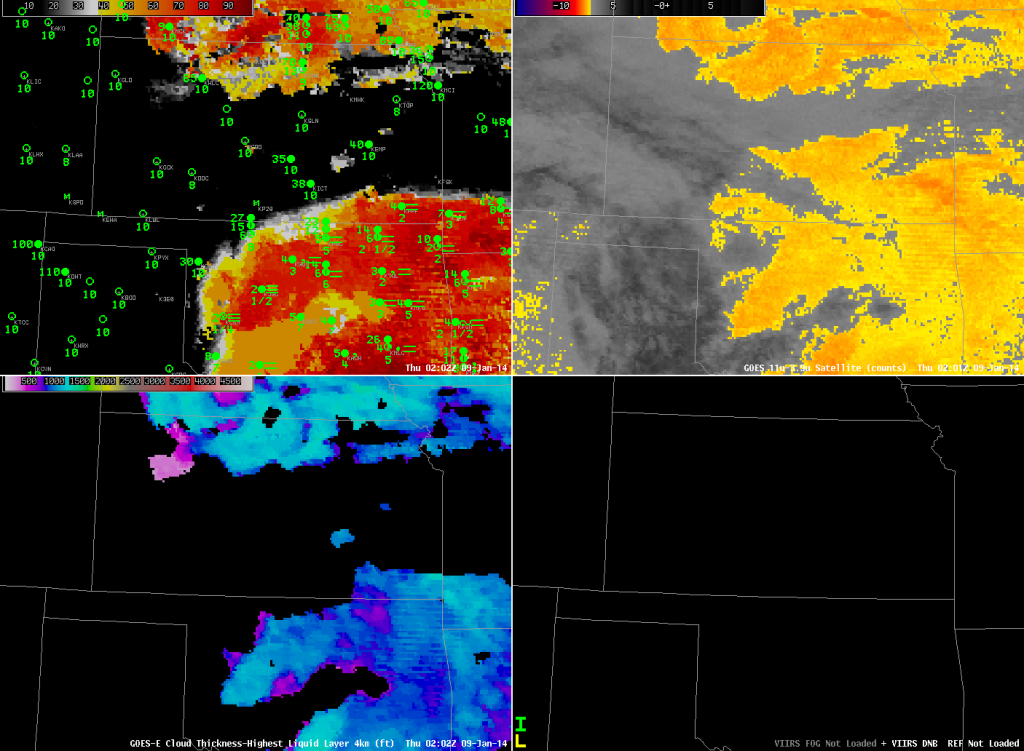

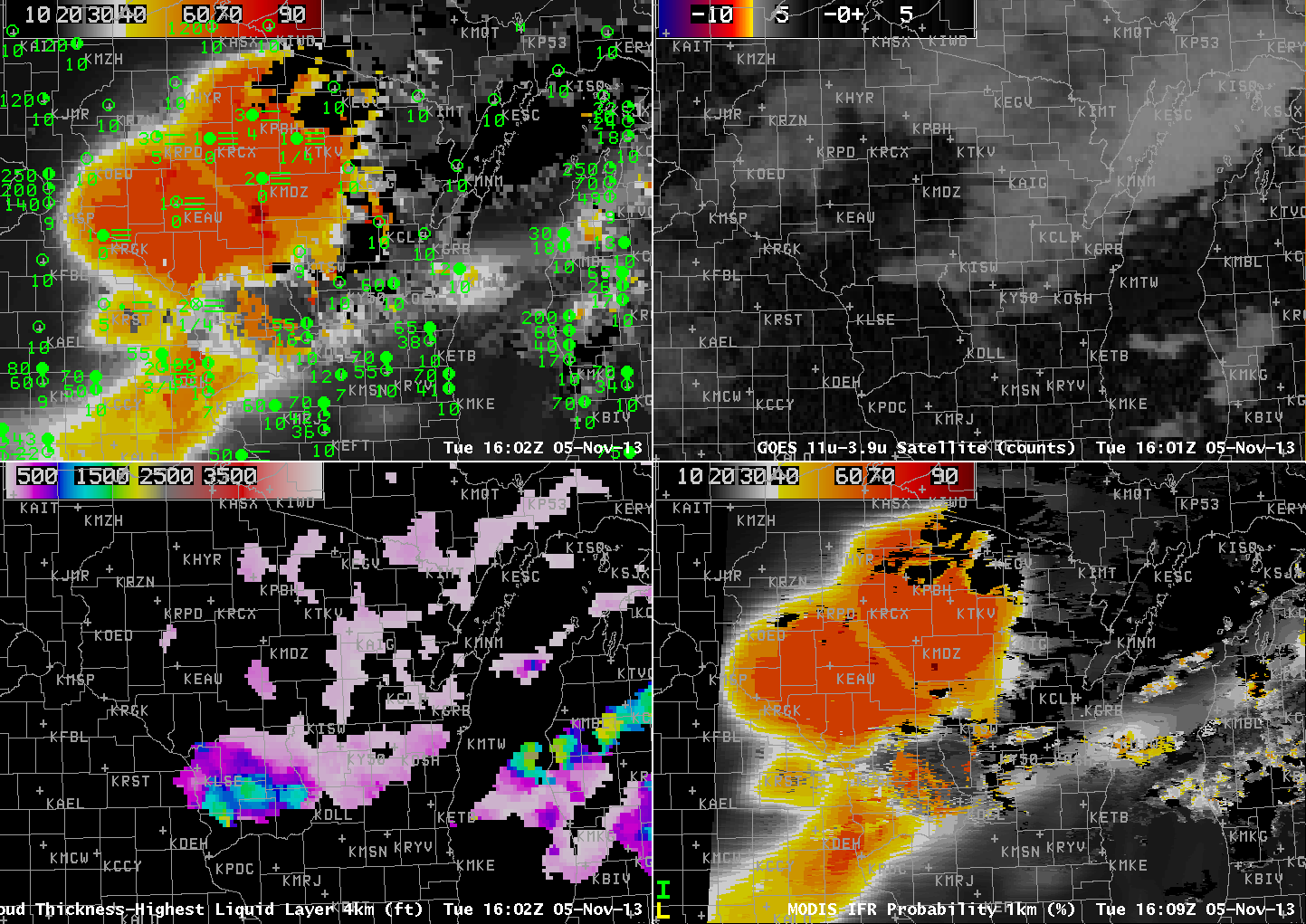

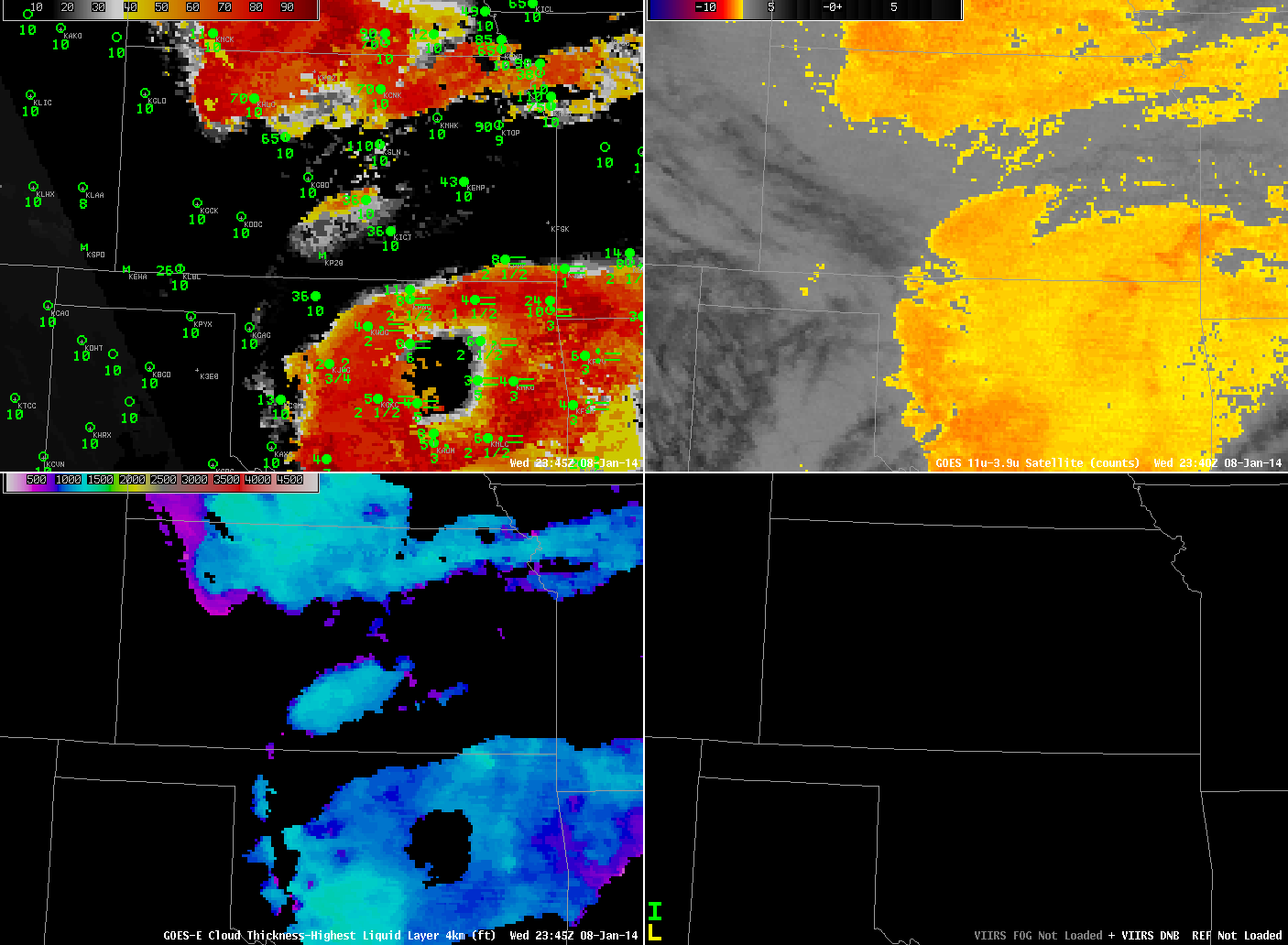

GOES-R IFR Probabilities from GOES-13 (upper left), GOES-13 Brightness Temperature Difference (10.7 µm – 3.9 µm) Fields (upper right), GOES-R Cloud Thickness from GOES-13 (lower left), Suomi/NPP Day/Night Band (lower right), ~2345 UTC 8 January 2014 (click image to enlarge)

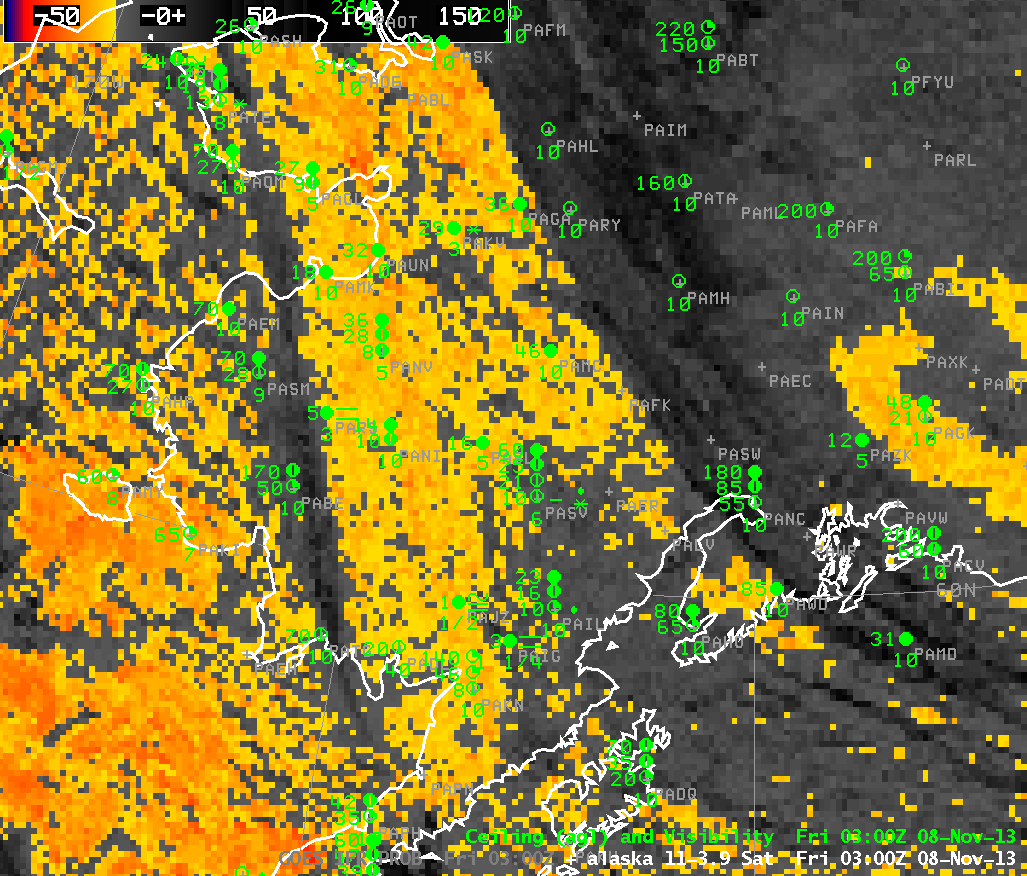

IFR Conditions developed over portions of Kansas and Oklahoma (and adjacent states) overnight. How did the GOES-R IFR Probability field diagnose the development of this event? At ~0000 UTC, the traditional method of low stratus/fog detection (Brightness Temperature Difference) showed two regions over the Plains, one centered over Oklahoma, and one over the Kansas/Nebraska border. IFR Probabilities at the same time covered a smaller area; Wichita in particular had low IFR Probabilities despite a brightness temperature difference signal, and Wichita did not report IFR conditions at the time.

Note that high clouds are also present in the Brightness Temperature Difference field over western Kansas, the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, and New Mexico. In the enhancement used, high clouds are depicted as dark greys.

By 0200 UTC (above), the high clouds have moved over parts of Oklahoma and Kansas. Consequently, there are regions over central Oklahoma and south-central Kansas where the brightness temperature difference field is not useful in detecting low stratus/fog that is occurring. The IFR Probability fields suggest the presence of low clouds despite the lack of satellite data because the IFR Probability Field also uses output from the Rapid Refresh Model that suggests saturation is occurring in those regions. Model data are also used where satellite data suggest low clouds/stratus are present to delineate where surface ceilings/visibilities are congruent with IFR conditions. As at 2345 UTC, Wichita is not reporting IFR conditions, although the brightness temperature difference field suggests IFR conditions might exist. The IFR Probability field correctly shows low values there.

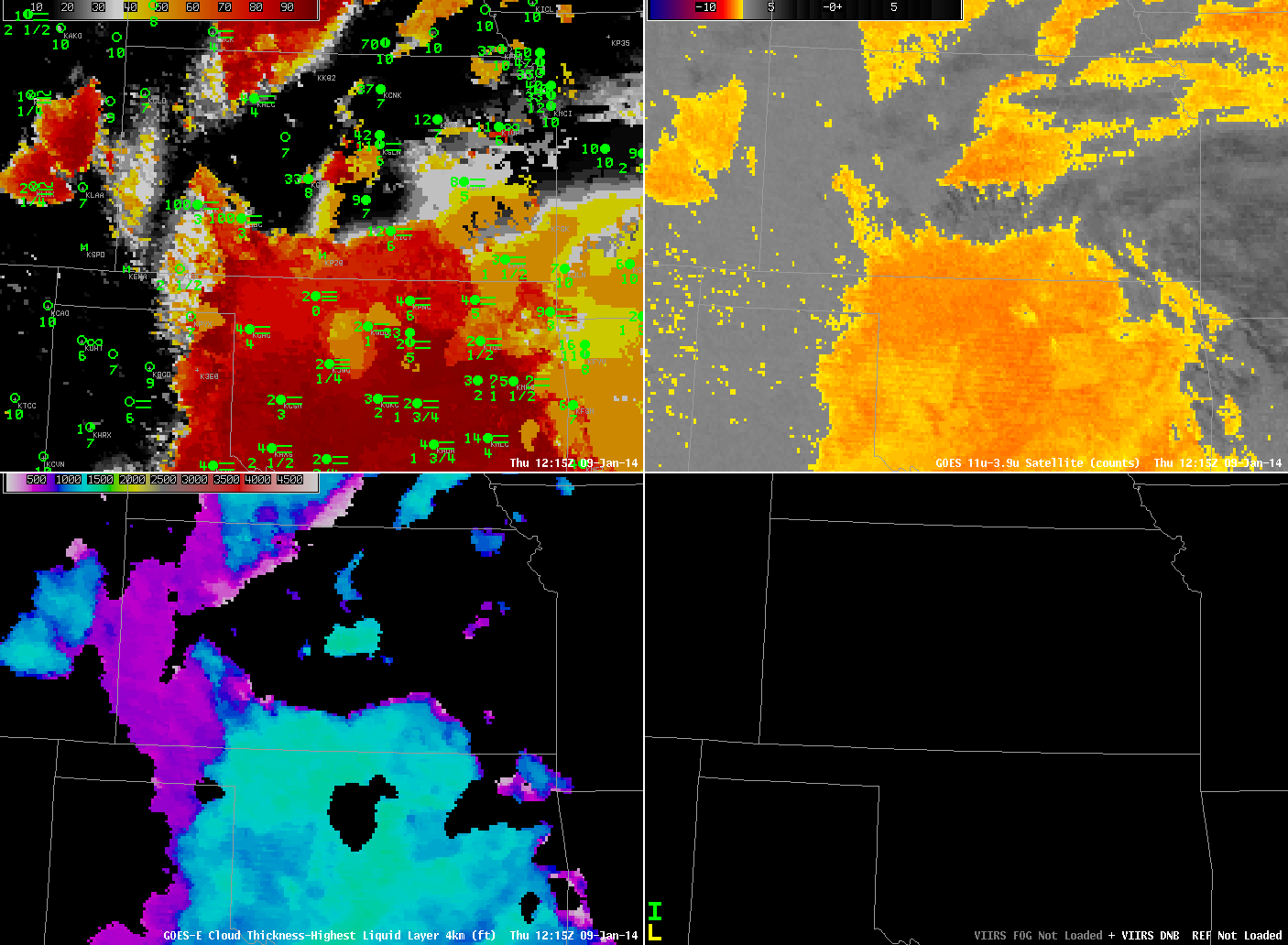

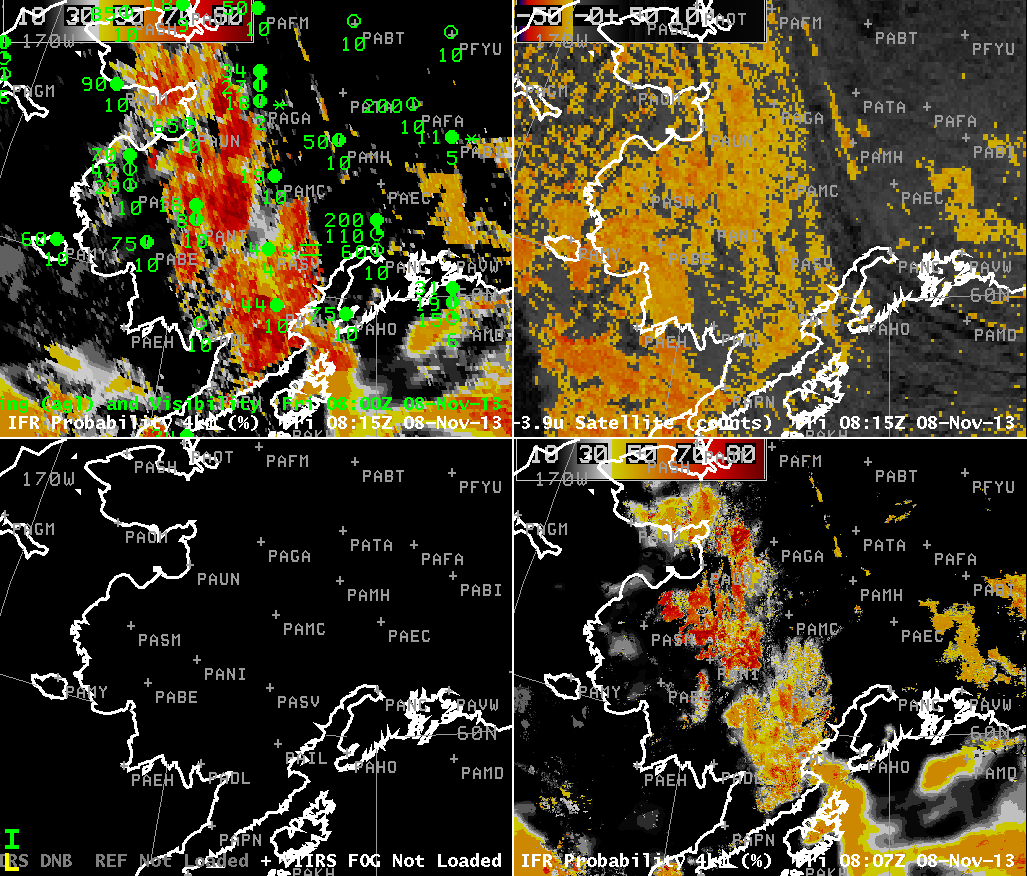

As above, but at 0802 UTC 9 January 2014. Suomi/NPP data is a toggle of Day/Night band and 11.35 µm – 3.74 µm brightness temperature difference (click image to enlarge)

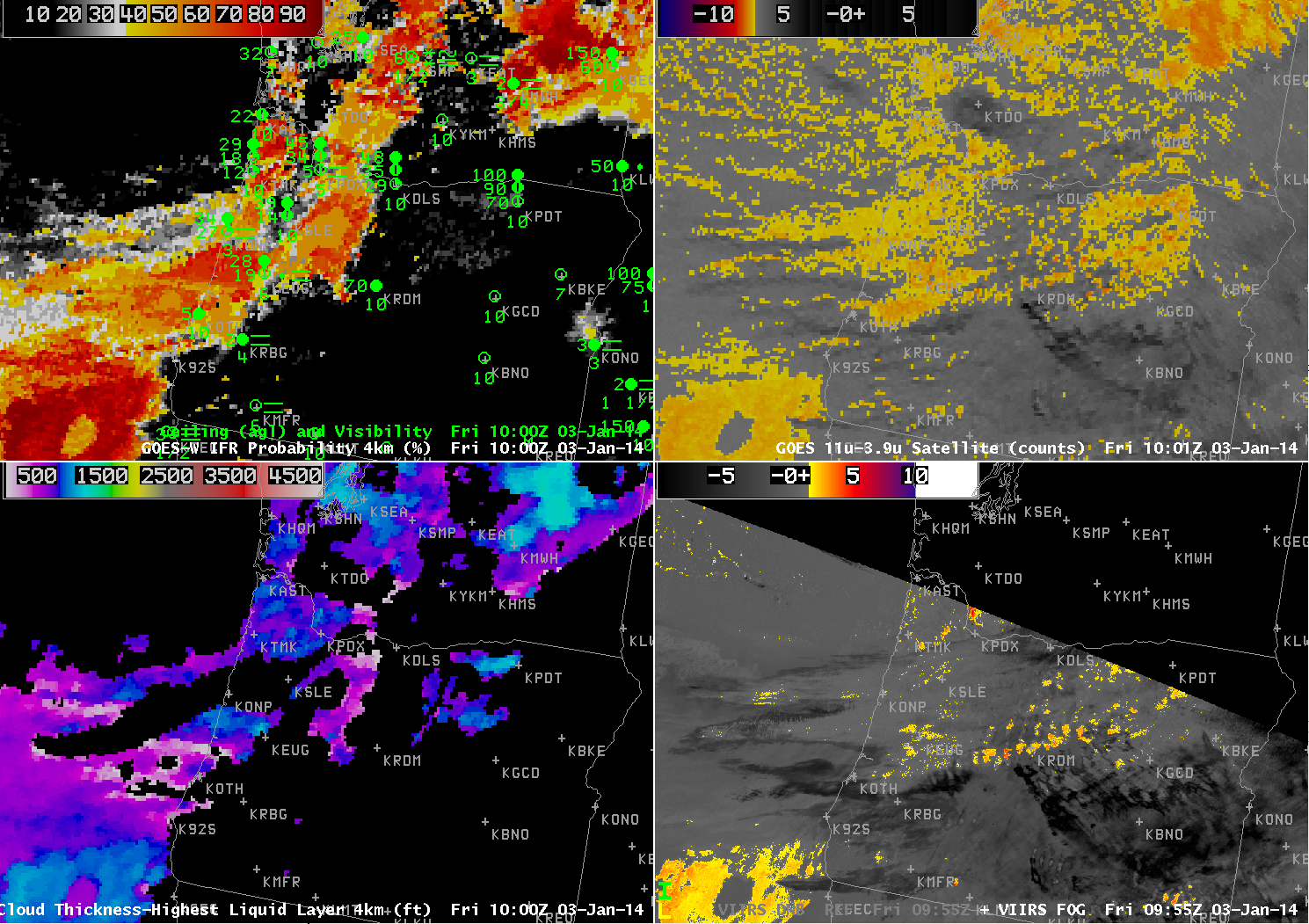

By 0802 UTC, high clouds have overspread much of Oklahoma, yet IFR conditions are occurring at several locations. IFR probabilities nicely depict the widespread nature of this IFR event. Probabilities are reduced in regions where high clouds are present because the algorithm cannot use satellite predictors of low clouds/stratus there. Both the Day/Night band and the brightness temperature difference field give information about the top of the cloud deck — it’s hard to infer how the cloud base is behaving. The addition of Rapid Refresh model information on low-level saturation helps better define where IFR conditions are present.

As above, but at 0945 UTC 9 January 2014. Suomi/NPP data is a toggle of Day/Night band and 11.35 µm – 3.74 µm brightness temperature difference (click image to enlarge)

By 0945 UTC, above, the time of the next Suomi/NPP overpass, the high clouds have started to move eastward out of Oklahoma. Consequently, satellite data can be used as one of the predictors in the IFR probability field, and IFR Probabilities over Oklahoma increase. By 1215 UTC (below), higher clouds have east out of the domain, and IFR Probabilities are high over the region of reduced ceilings/visibilities over Oklahoma. The algorithm continues to show lower probabilities in regions over Kansas where the Brightness temperature difference signals the presence of low stratus/fog but where IFR conditions are not present. Again, this is because the Rapid Refresh model in those regions is not showing low-level saturation.

Note in the imagery above how the presence of high clouds affects the GOES-R Cloud Thickness. If the highest cloud detected is ice-based, no cloud thickness field is computed. GOES-R Cloud Thickness is the estimated thickness of the highest water-based cloud detected. If ice clouds are present, the highest water-based cloud cannot be detected by the satellite. Cloud Thickness is also not computed during twilight conditions. Those occurred just before the first image, top, and about an hour after the last image, above.