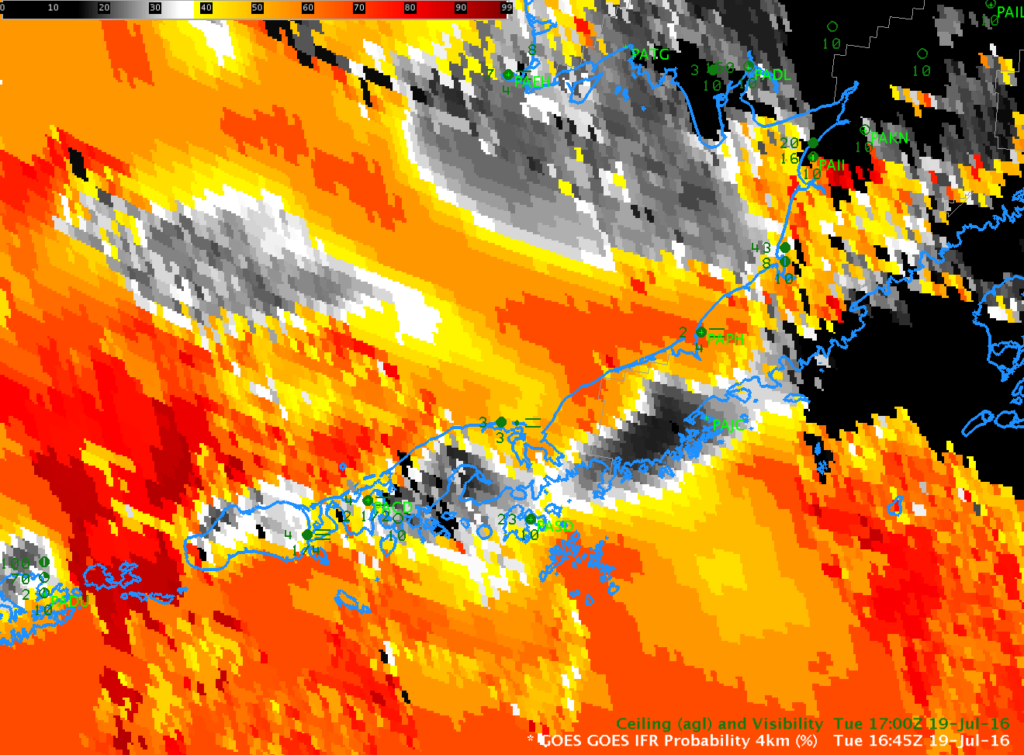

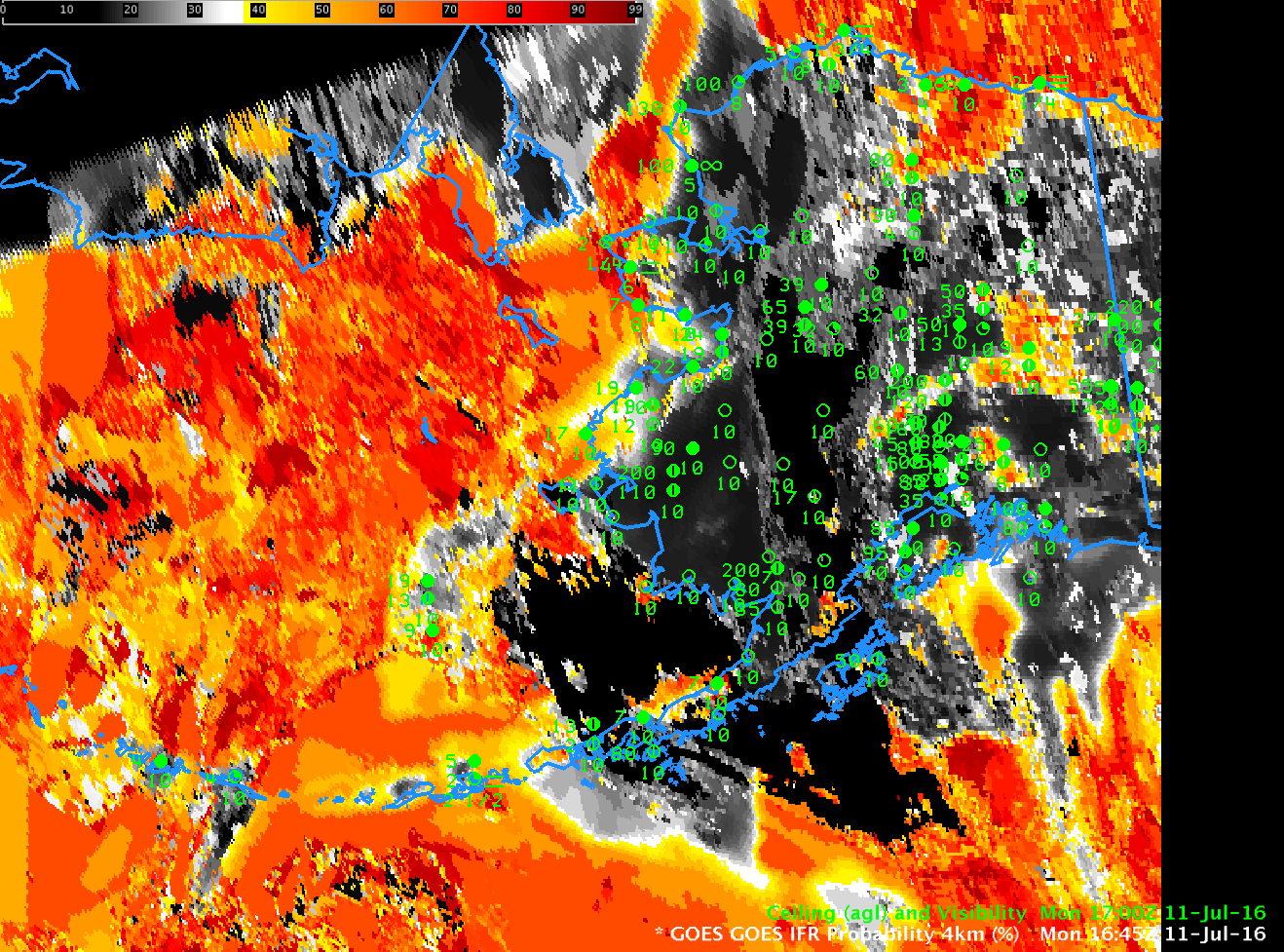

The animation above steps through the Night Fog brightness temperature difference (10.3 µm – 3.9 µm), the Nighttime Microphysics RGB (which RGB has as its green component the Night Fog brightness temperature difference) and the GOES-17 IFR Probability fields at 1100 UTC on 24 September 2021. (Note that the Night Fog Brightness Temperature difference and Night Microphysics RGB are at reduced resolution)

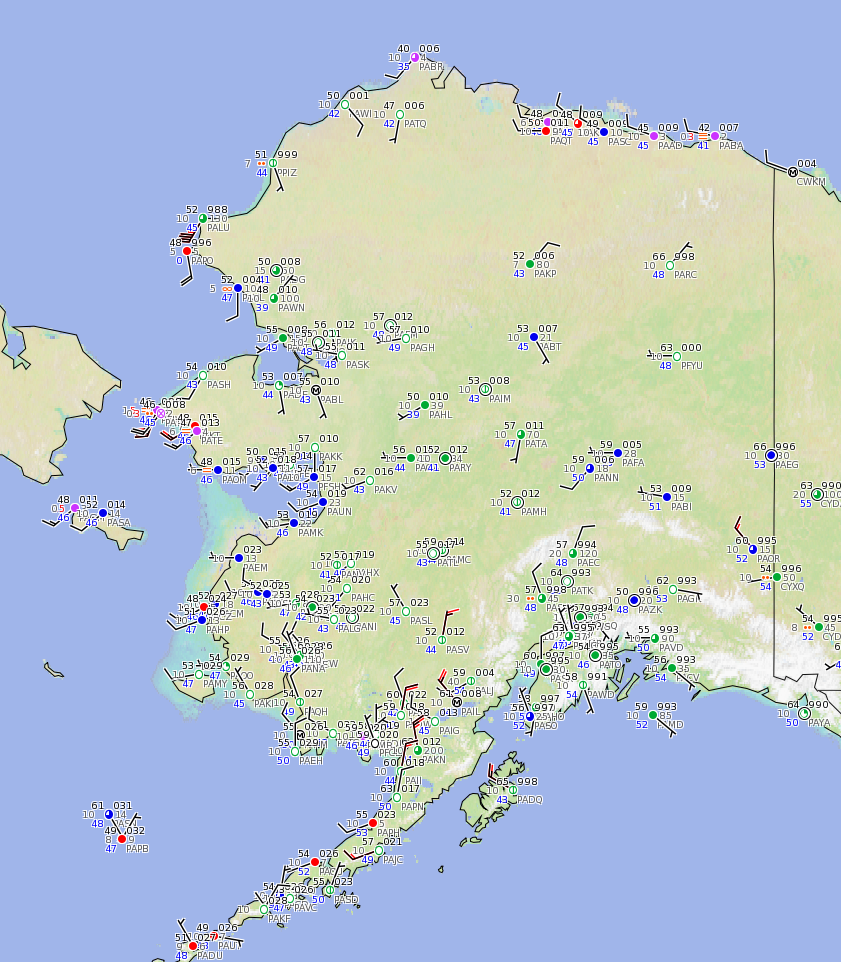

A low pressure system is moving onshore through southeastern Alaska. The animation includes two regions that demonstrate particular strengths of the IFR Probability field: over inland and coastal southeastern Alaska, east of Anchorage and west of Yakutat, where low clouds are diagnosed under the multiple cloud layers; over western Alaska where low clouds are diagnosed by the brightness temperature difference field — and color-enhanced as cyan/blue — but where fog observations are not occurring. Over western Alaska, model data allows the IFR Probability to screen out the region of elevated stratus.

Animations of the brightness temperature difference field, the night time microphysics RGB and the IFR Probability are shown below.

On this day, GOES_17 IFR Probability fields were better able to highlight regions of low ceilings and visibilities over Alaska by combining the strength of satellite detection of clouds and the ability of Rapid Refresh model simulations to predict where low-level saturation is most likely. Note that in the animation of the IFR Probability fields there are slight changes on the hour that are related to incorporation of new model output into the computation of the fields.

GOES-17 IFR Probability fields are slated to be operational as of 13 October 2021.