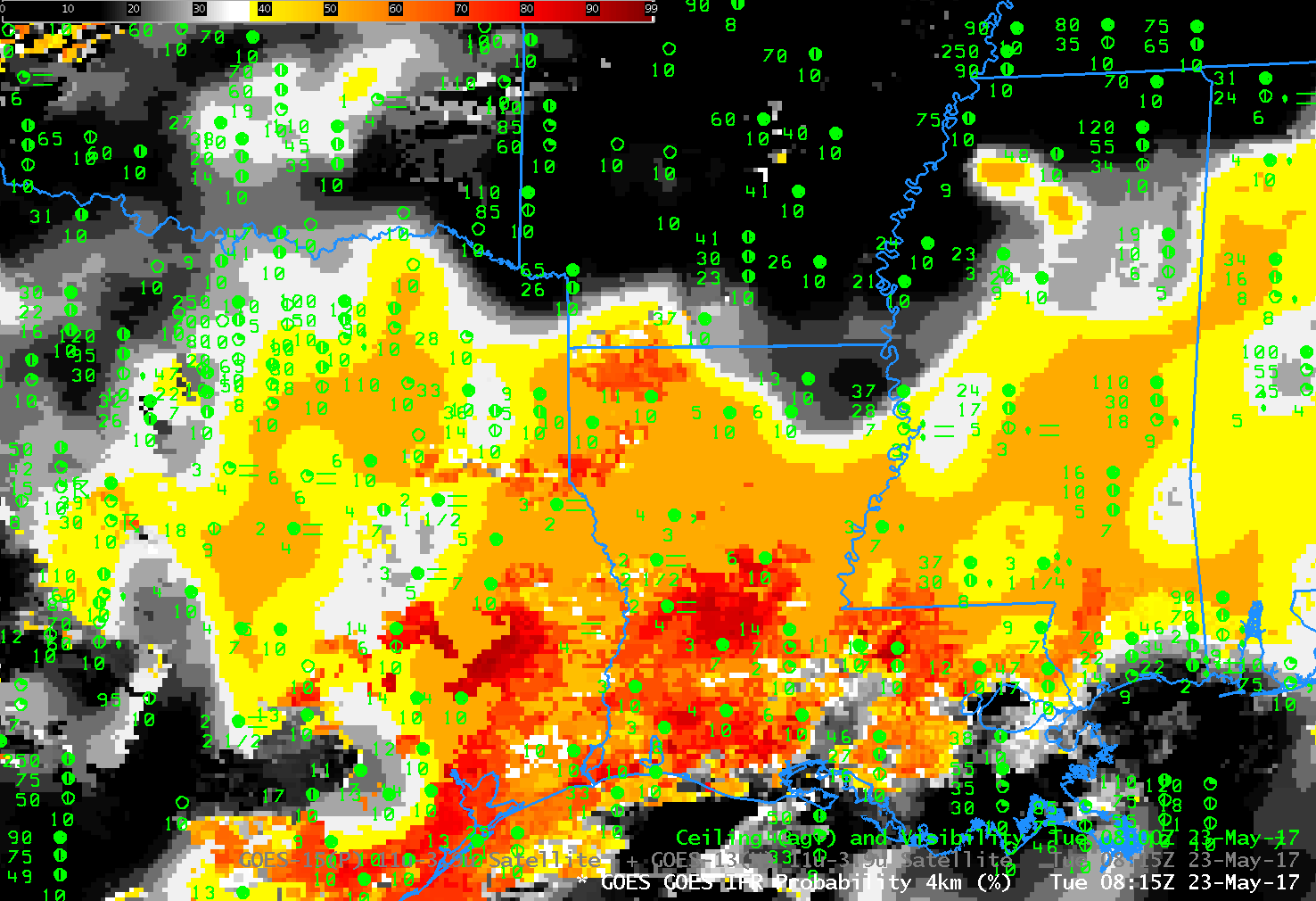

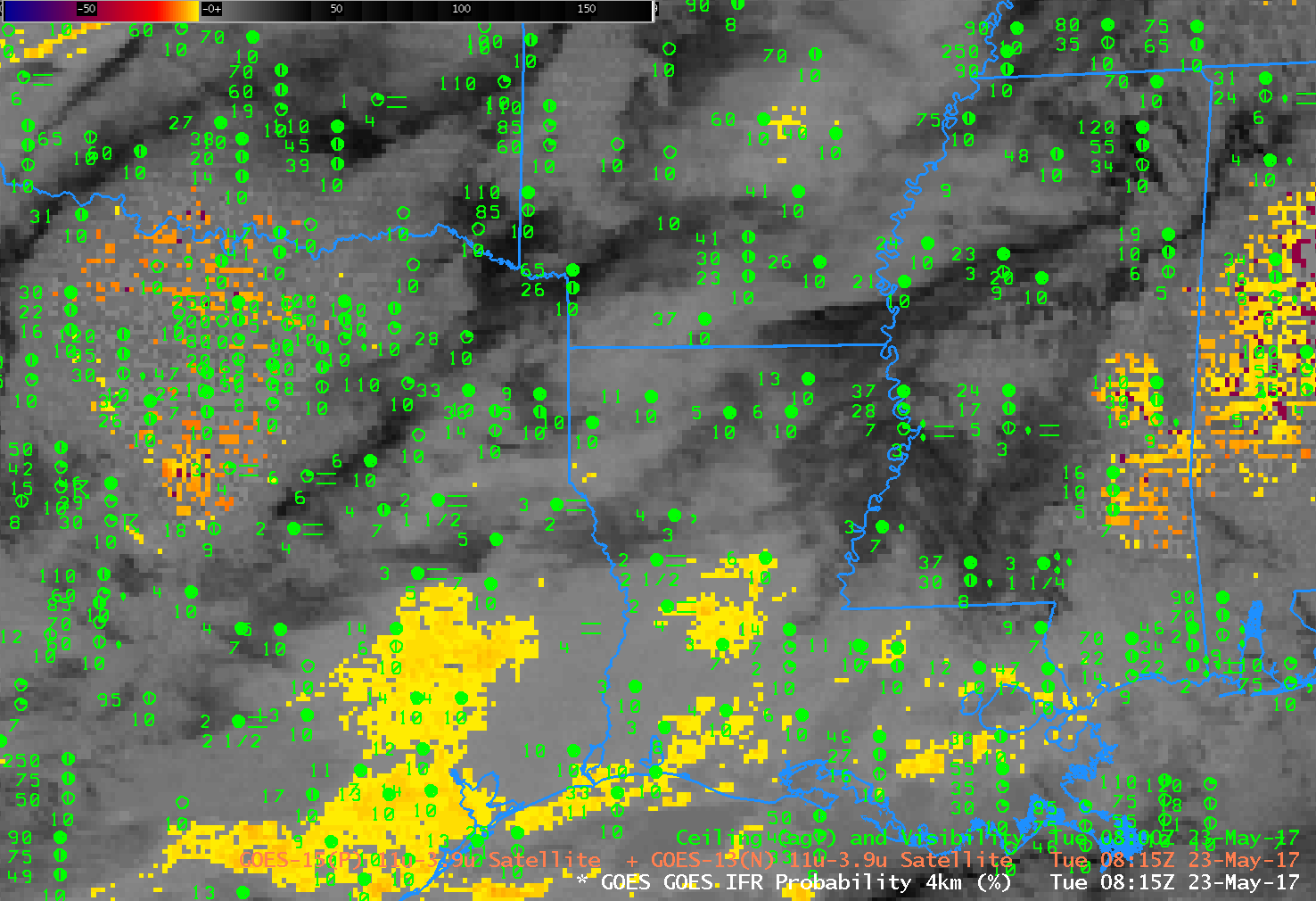

GOES-13 Brightness Temperature Difference (3.9 µm – 10.7 µm) Values at 0815 UTC on 23 May 2017 (Click to enlarge)

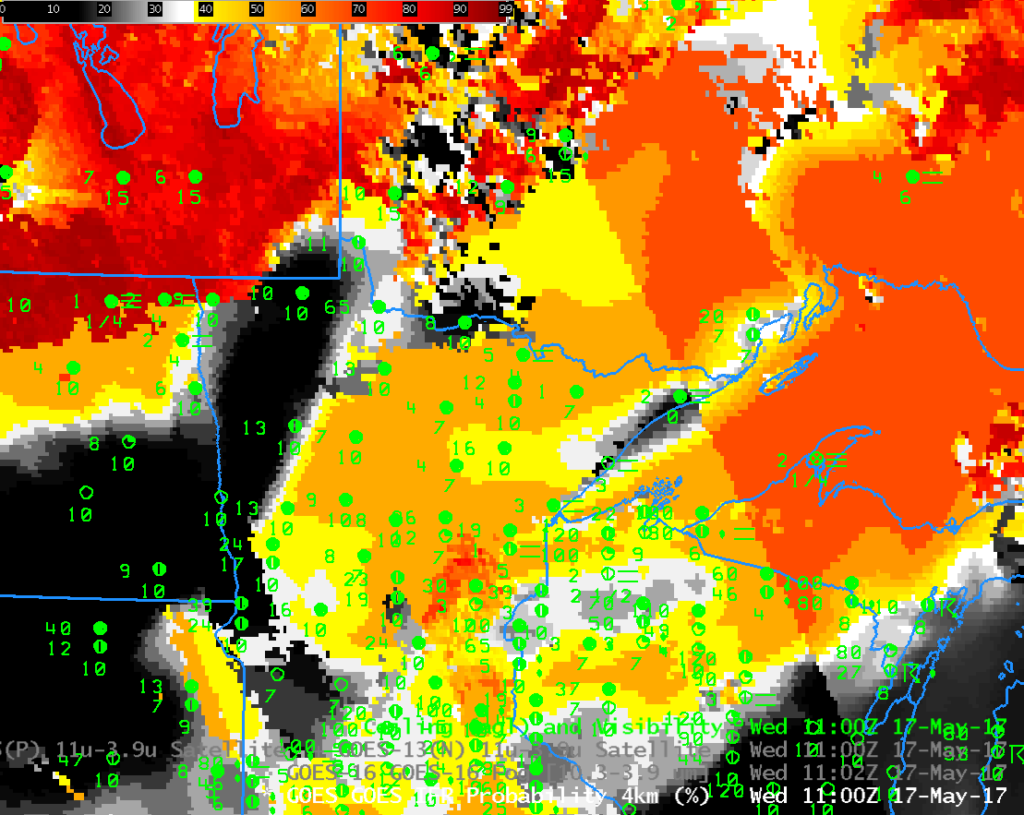

Note: GOES-R IFR Probabilities are computed using Legacy GOES (GOES-13 and GOES-15) and Rapid Refresh model information; GOES-16 data will be incorporated into the IFR Probability algorithm in late 2017

The legacy method of detecting fog/low clouds from satellite is the Brightness Temperature Difference product that compares computed brightness temperatures at 3.9 µm and at 10.7 µm. At night, because clouds composed of water droplets do not emit 3.9 µm radiation as a blackbody, the inferred 3.9 µm brightness temperature is colder than the brightness temperature computed using 10.7 µm radiation. In the image above, the brightness temperature difference has been color-enhanced so that clouds composed of water droplets are orange — this region is mostly confined to southeast Texas. Widespread cirrus and mid-level clouds are blocking the satellite view of low clouds. IFR and near-IFR conditions are widespread over east Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. The GOES-R IFR Probability field, below, from the same time, suggests IFR conditions are likely over the region where IFR conditions are observed.

This is a case where the model information that is included in this fused product (that includes both satellite observations where possible and model predictions) fills in regions where cirrus and mid-level clouds obstruct the satellite’s view of low clouds.. As a situational awareness tool, GOES-R IFR Probability can give a more informed representation of where restricted visibilities and ceilings might be occurring.

IFR Conditions continued into early morning as noted in this screenshot from the Aviation Weather Center.