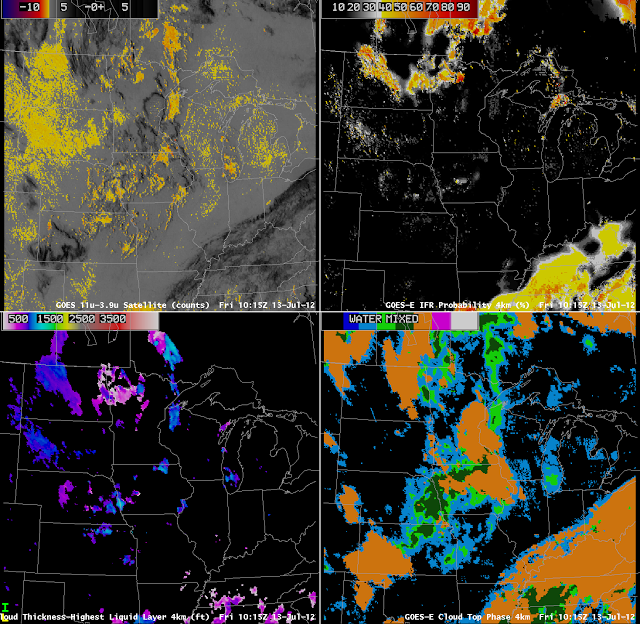

The figure above shows cloud thicknesses around 1000 feet near Omaha, Nebraska, in a region where cloud phase products suggest water clouds and supercooled clouds with small patches of cirrus, suggestive of clouds that might not be stratiform. The cloud thickness algorithm (the algorithm predicts the depth of the highest liquid layer) works night and day, although not in times of twilight.

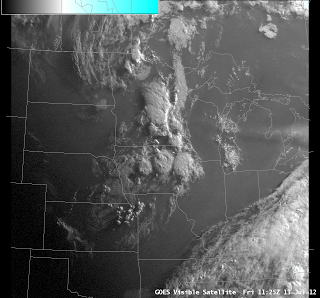

Note also in the image the many false positives in the traditional brightness temperature difference product over South Dakota. This region shows very low IFR probabilities, in contrast to the region over North Dakota where IFR probabilities are higher and where fog/low stratus is more likely, given the satellite image from 1125 UTC below. None of the widely-spaced stations in the Dakotas reported IFR conditions; there were some reports in northwestern Minnesota, however.

|

| Visible GOES-East image, 1125 UTC on 13 July, with a low-light enhancement applied. |

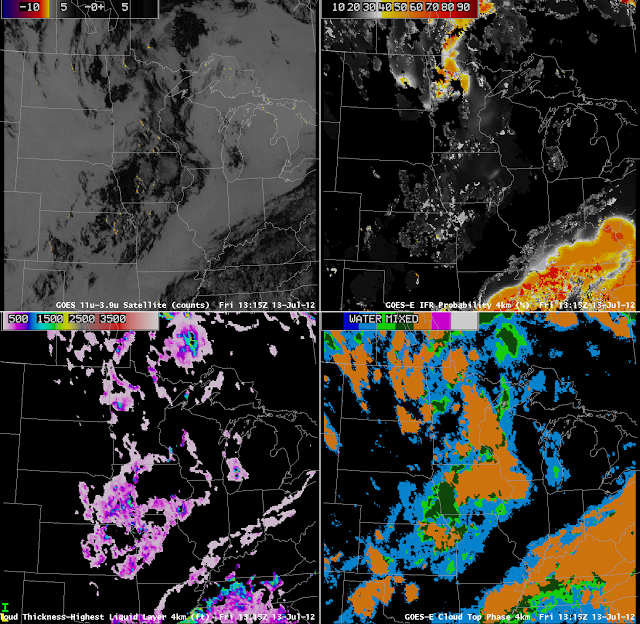

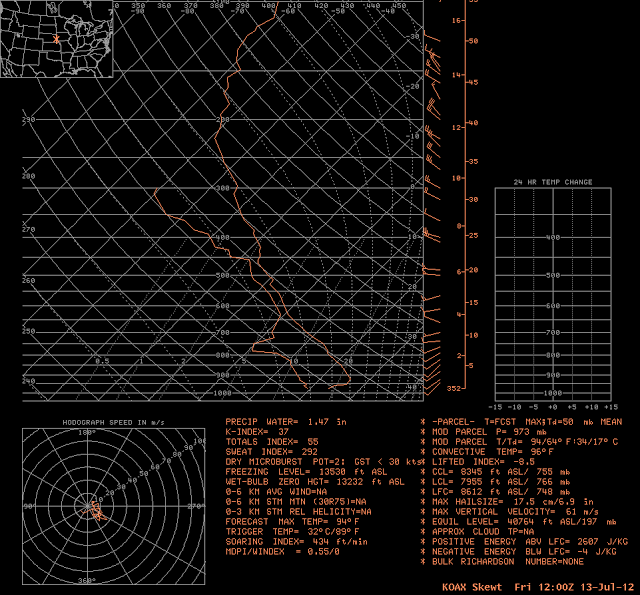

At 1315 UTC, during daytime, cloud thickness products show somewhat thinner low clouds in a region of very low IFR probability. The sounding from Omaha, bottom, suggests convective, not stratiform, clouds are present. The GOES-R Cloud Thickness product is produced assuming a stratiform cloud, and results are more likely to be erroneous for situations with clouds that are more cumuliform. Cloud thickness is derived in part by dividing the liquid water path by liquid water content: for fog and low stratus, the liquid waer content value is 0.06″ per the meteorological literature. If the clouds are actually non-stratiform, the assumed liquid water content may not be accurate. Remember that the cloud depth product was designed to augment the fog/low stratus probability to assist in determining how thick the fog is, and therefore how long it will take to dissipate during the day. Use the cloud depth with caution if the clouds in question are not stratiform.

|

| Skew-T/Log-P thermodynamic diagram from Omaha, Nebraska (KOAX) at 1200 UTC on 13 July 2012 |